RESTORATION

After years of playing drums and percussion, I have become captivated by the rich history of my craft. Along the way, I have acummulated a growing collection of percussion instruments.

Feel free to contact me at n[email protected] should you have a question, need restoration advice, or just want to share your passion with vintage percussion instruments. I'd love to hear from you.

After years of playing drums and percussion, I have become captivated by the rich history of my craft. Along the way, I have acummulated a growing collection of percussion instruments.

Feel free to contact me at n[email protected] should you have a question, need restoration advice, or just want to share your passion with vintage percussion instruments. I'd love to hear from you.

My Restorations

1920's Ludwig 4-in-1 Whistle

Early 1920's Ludwig 4-in-1 Whistle owned by musician/poet Dale Wimbrow

Noble J. DilgerNoble in 1969

|

1917 Ludwig & Ludwig drum restoration project:

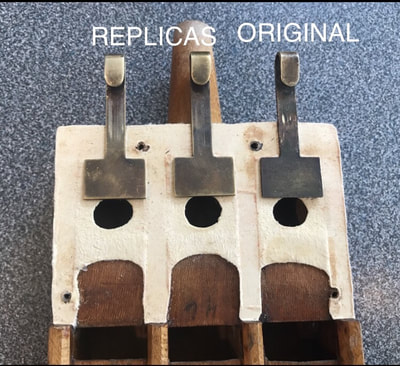

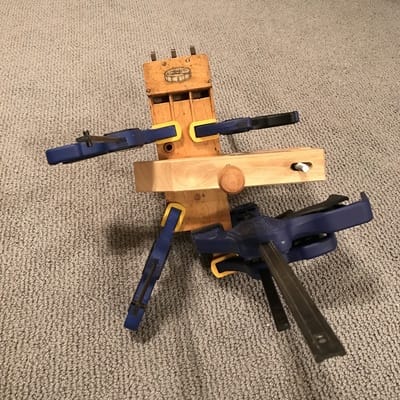

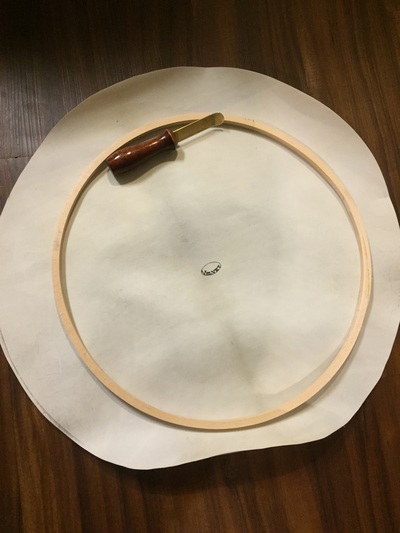

My restoration of this drum took me on an exciting journey, that eventually connected me with the family of the original owner, who was a solider in WWI and played under the famous John Phillip Sousa. In 2012 I began the ambitious endeavor of restoring my 1917 Ludwig & Ludwig drum, that I had obtained through an online auction. I had originally wanted the drum because it was a rare type of drum that Ludwig & Ludwig called a “rope-rod” drum (where the drumheads are pulled tight by a mixture of ropes and thumb screws). I soon learned that this drum had a unique fountain pen inscription written onto the drumhead by the original owner that included the owner's name, military unit, and the date, which suggested the owner was a WWI soldier, and member of the famous Navy Band. The drumhead and inscription, however, had been quite violently ripped and tattered over the years. (see damaged drum left) THE DRUM Knowing that my drum belonged to a specific WWI soldier gave me extra motivation to restore both the drum and the top drumhead. The drum itself was in bad condition when I first purchased it. It was a mess of “dust & rust”, but luckily it was not missing any parts. It had deteriorated, but had not suffered any bad restorations or any other molestations besides the effects of time. I set out to remove and polish all the brass and steel parts. The roller hooks that attach the ropes to the hoops were rusted fairly badly, and I chose to replace them with identical vintage ones rather than removing the rust on the originals (I may someday use the originals). The drum shell was slightly warped, but still functional. After being cleaned thoroughly, a little “Olde English” brought much of the origin luster back to the shell. I had the original rope, but it was ripped. I was able to find modern rope that was perfectly identical. I then tried to age the rope by giving it more of a yellowish brown color. It created a lot laughs among myself and my friends, but I actually soaked the rope in soy sauce to do this. It worked better than dye, but I didn’t realize it would take a month for it to NOT smell again! Assembling the drum from scratch was and still is a very complicated matter given the complicated arrangement of ropes, hooks, and rods. After then replacing the drumheads and the snares (the original snares were actually red fabric or “weatherproof” snares), the restoration was complete. (see restored drum left) THE RIPPED DRUMHEAD I had first used tape to partially fix the tattered drumhead, and to be able to actually read what was written on it. I then got the idea that I could try to patch the entire drumhead back together. To my knowledge, this has never been done with a drumhead that has multiple rips in it. I learned that the fountain pen inscription qualifies as WWI “trench art”, and decided it was worth saving. The work required was much closer to the work of a museum conservationist, than a drum restorer. I learned on the internet about how calfskin parchments are repaired, but most of my repair work was done with my own ideas. The “patches” that I used were made of scrap pieces of calfskin, so that —in theory— the patches would expand and contract with humidity along with the area of calfskin they were glued to. Many of the patches were cut into the exact shape of the rip they were being glued onto, and then moistened in water to make them flexible. Museum conservationists use a home-cooked organic glue that moves with the calfskin during humidity changes, but I instead used Superglue, because it quickly bonds to calfskin, even if it is wet. I carefully wetted all the calfskin parts I was working with to make them pliable, and then off and on over the course of a few months I managed to glue over one hundred patches onto the back of the drumhead. I’m still trying to repair one big rip, but its difficult fitting it onto the hoop. HISTORY : THE BACKGROUND OF THE DRUM The inscription on the drumhead said the drum belonged to a “N. J. Dilger”, December 20th, 1917-- roughly 4 months after the United States entered the war. This was very exciting information. I was very curious if the drum had been used at the famous Great Lakes Naval Base, because I had a family member that has been stationed there in the past. Through the wonder of the internet, I was able to do a lot of “history detective” work. It wasn’t easy, but I managed to learn that the soldier was Noble Joseph Dilger. Even more, I managed to track down the phone number of his daughter (now in her 80’s) and give her a call. She was shocked and surprised to know that someone had called asking about her father, and a drum he owned (It had apparently been in the family for a long time, and then somehow given away or sold). She further explained to me that her father was a 25-year old WWI drummer who described his occupation as "stenographer" when he enlisted. He played with the USN band at Great Lakes Naval just north of Chicago under the baton of John Philip Sousa! Sort of perfect for my interests--his wife was a pianist in silent films. She died at age 108 and it was her obituary that finally gave me the confirmation of these facts. While this type of drum doesn’t seem to have been standard issue, I can only presume Noble Dilger purchased it for himself, and then proudly inscribed his name on it. I corresponded with various members of the Dilger family, who were grateful for the restoration of the drum, and who ironically didn’t live far from my hometown of Chicago. |